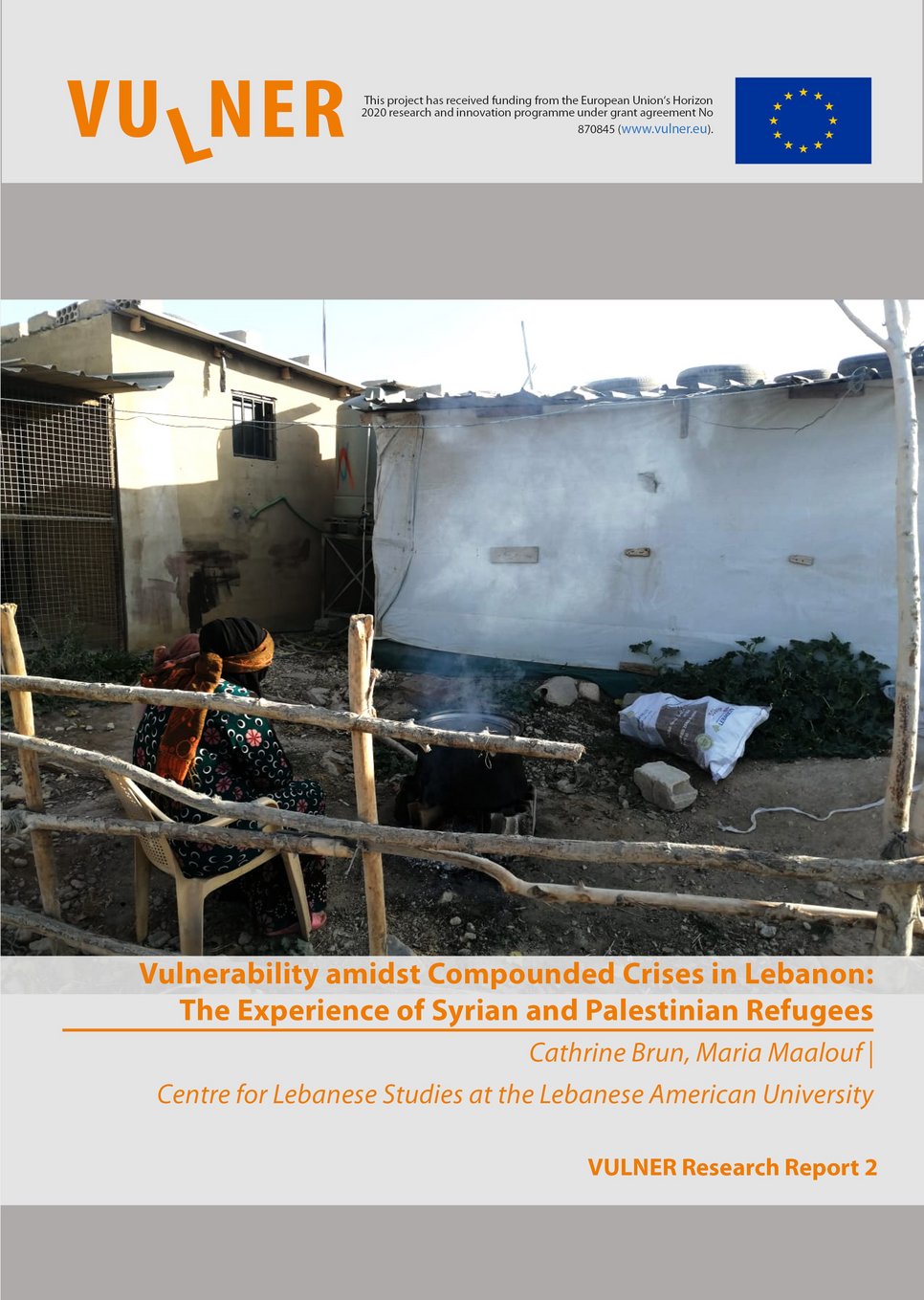

Vulnerability amidst Compounded Crises in Lebanon: The experience of Syrian and Palestinian Refugees

Research report on the experiences of migrants seeking protection in Lebanon - by Cathrine Brun and Maria Maalouf

The VULNER research project’s objective is to reach a more profound understanding of the experiences of vulnerabilities of migrants applying for asylum and other humanitarian protection statuses, and how they could best be addressed. It therefore makes use of a twofold analysis, which confronts the study of existing legal and bureaucratic norms and practices that seek to assess and address vulnerabilities among migrants seeking protection, with migrants’ own experiences.

In this second report from the Lebanon case study of the VULNER project, the objective is to understand the relationship between experiences of vulnerabilities among displaced populations and the legal and bureaucratic frameworks in place. With the help of insights from Syrian Refugees, Palestinian Refugees from Syria and Palestinian refugees residing in Lebanon we explore how vulnerabilities are constituted and may increase or decrease as a result of the legal and bureaucratic framework they encounter. The report builds directly on the first phase of the project and the first report from Lebanon (El Daif et al. 2021) in seeking to understand the experience of vulnerability by refugees. In the first report, which focused mainly on the legal and bureaucratic framework, we showed that in Lebanon, there is no legal protection for refugees, there is no asylum law and Lebanon considers itself a transit country rather than a host country. As a result, different refugee groups are treated differently: Most Palestinian Refugees residing in Lebanon have legal residency and a work permit to access a limited number of occupations, most of the Syrian refugees and Palestinian refugees from Syria we interviewed did not have legal residency in Lebanon. Yet all displaced populations – regardless of their residency status and despite their protracted residence in the country – officially reside in Lebanon temporarily.

In this second stage of the project we conducted 57 interviews with refugees – Syrian refugees (34), Palestinian refugees residing in Lebanon (9) and Palestinian refugees from Syria (14). We also interviewed representatives of seven organisations working directly with refugees. In the report, we explore the relationship between refugee experiences and policy frameworks at different scales. First, we analyse – at a micro level – refugees’ understandings and experience of vulnerability. Second, and moving to a meso level, we discuss research participants’ encounters with the legal and bureaucratic frameworks that concern them. Finally, we address the relationship between the experiences of vulnerabilities and the macro level, namely the global and national frameworks relating to Syrian and Palestinian refugees in Lebanon. The interviews were conducted in the context of compounded crises in Lebanon. We show in the report that living with displacement in the context of an ongoing deep financial and governance crisis, the Covid pandemic and the aftermath of the Beirut explosion in August 2020, influence the ways in which vulnerabilities are experienced. ‘Vulnerability’ is a contested concept in Lebanon where it is frequently used in different ways in national and international frameworks and by organisations assisting refugees, yet it does not have a clear translation in Arabic. In our interviews with refugees and representatives from organisations, we found a wide range of understandings that can be divided into two meanings. The first meaning is a categorical understanding based on vulnerability determined from personal characteristics such as age, gender, disability and sexual orientation. The second meaning refers to a more dynamic, situational and contextual understanding focusing on susceptibility to harm and threat to interest and autonomy that can happen to any individual at some point in time.

Regarding the individual experience of vulnerability at the micro level, the report discusses how vulnerability is experienced based on people’s displacement histories, their legal residency status in Lebanon, categories such as age, gender and health. We also examined specific conditions related to employment and livelihoods, housing and social networks. Exploring the different dimensions that research participants shared with us, we find, first, that there is an interaction of legal and socio-economic factors that create the individual experience of vulnerability. Second, we find that in a context of compounded crises where most people experience some level of vulnerability, it is the interaction of different factors that produces individual vulnerability outcomes and changes vulnerability over time.

At the meso level the report shows that there is an institutional void in Lebanon’s refugee governance. Refugees do not consider the Lebanese state institutions as a site of protection or assistance. No-one of the research participants felt they have any say and influence over the decisions that impact their presence and future in the country. For support, refugees rather seek towards international and local organisations than the state, but found it hard to access them and it was difficult to understand who is eligible for assistance and consequently what vulnerability criteria are operating at any given time. For many research participants, what is left for support are informal connections and networks. However, friends and family are often in the same dire situation and can offer limited material support. Refugees can only mobilise a constrained agency in the encounter with different institutions because there is a limit to refugees’ ability to counter the processes that cause vulnerability.

This brings us to the macro level and the role of national and global policies and frameworks in producing of vulnerabilities. Analysing policy processes, donor meeting outcomes and reports and instruments, we show that the humanitarian system and the international community missed the opportunity to hold the Lebanese government to account in order to secure refugees’ rights. The international community has an interest to prevent refugees from moving towards Europe by keeping them where they are. This interest comes together with the humanitarian approach of neutrality, impartiality and independence resulting what can be seen as an indirect endorsement of the Lebanese state’s approach to refugees as exceptions, matter out of place and devoid of right to a say in decisions taken over their lives. We conclude that refugees continue to stay in Lebanon with ever increasing vulnerabilities and with limited prospects for finding a solution to their plight.

Download the full report here.